OPINION: Americans don’t understand the policies behind the party

By Vishaka Priyan ‘26

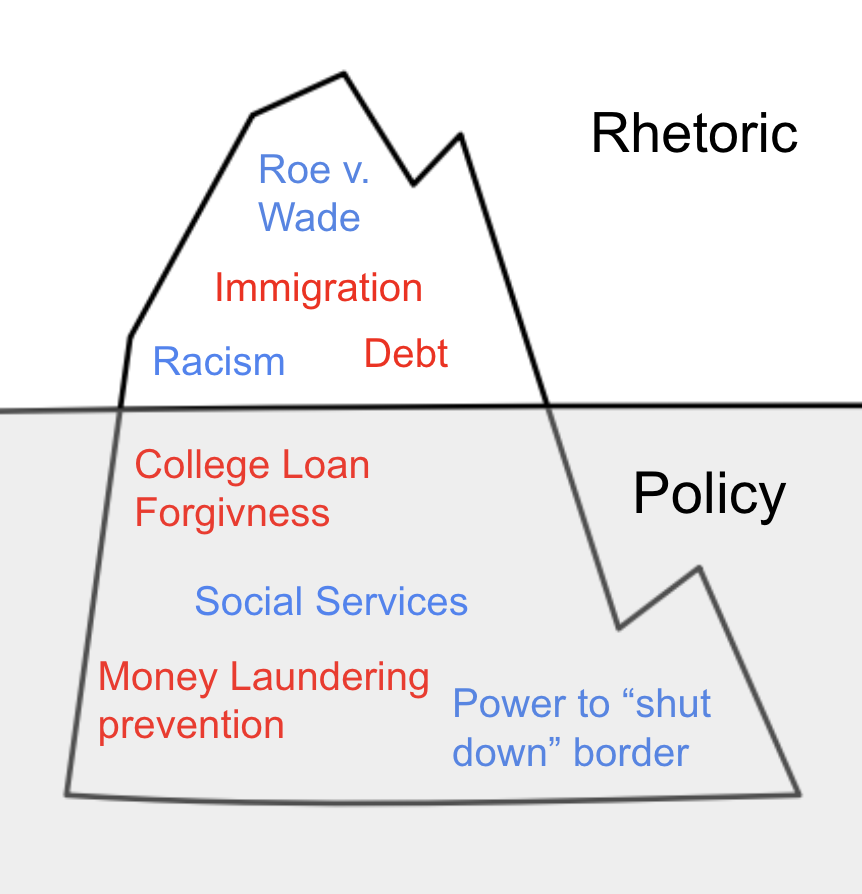

Photo by Vishaka Priyan ‘26

Since I first became aware of the different political perspectives in our country, I've found myself aligning with more liberal ideology.

When I was younger, my inclination towards the left stemmed from hearing that it was associated with kindness and openness. As I grew older, my affiliation deepened, partly due to my disagreement with former president Donald Trump's rhetoric and actions, and my stance on many social issues.

However, as ashamed as I am to admit it, I have never known exactly why I consider myself a Democrat. Now, I’m speaking purely on a policy-based level. I understand that certain lines simply can’t be crossed, and on a basic level, the general principles promoted by the Democratic party align with my own.

But, politics aren’t that simple.

It struck me how little I knew about my own political party during Biden’s State of the Union Address a couple of weeks ago. I heard him mention a particularly strict border policy. One that would allow Border Control the power to shut down the border after more than 5000 migrants entered the country in 7 days; for reference, an average of 6500 migrants cross the border per week.

I remember thinking, “This doesn’t sound like a Democratic bill.” All I’d been hearing for the last five years from the left was that Trump’s border policies were inhumane, and from the right that Biden was soft on border control. This policy didn’t seem very “humane" or “soft” to me.

I realized that I knew a lot less about my own political party than I ever thought I did. Despite being educated at private schools–who preached the importance of voting–all my life, I didn’t have any knowledge of the bills and policies being pushed by Republicans or Democrats beyond the few that were heavily covered in the media I consumed.

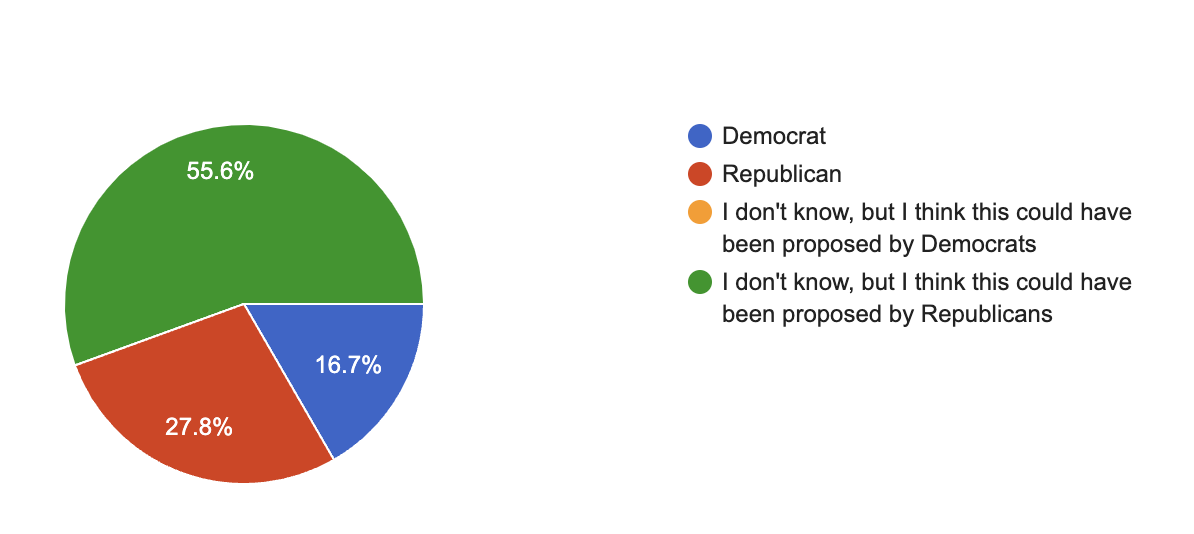

Furthermore, I don’t think my experience is unique. I believe that it's shared by many Catlin Gabel School (CGS) students and many Americans. A concerning survey done of 18 randomly selected CGS Upper School students, showed that only 3 of them were aware that the bipartisan border policy mentioned above was one proposed by the Democratic party.

A pie chart demonstrating which party 18 CGS Upper School students thought proposed the bipartisan border policy.

Only 4 respondents correctly attributed a bill that requires federal grants to notify their beneficiaries of their right to be free from religious discrimination to the Republican party. But this problem is not confined to CGS, a recent study found that American voters are up to 30% more likely to be less aware of news unfavorable to their political party.

A pie chart demonstrating which party 18 CGS Upper School students thought proposed the religious discrimination prevention clause for federal grants.

“We can obviously make better decisions when we understand a policy and its consequences,” said Amanda Williams when asked about the importance of informed political stances. Williams gave the example of Measure 110 in Oregon which was passed to decriminalize drug possession without understanding that the state’s resources were not yet equipped to handle the change. The consequence of this is that the public now thinks decriminalization will never work and is eagerly supporting the repeal of Measure 110. In the words of Williams, “That’s a loss.”

The implications of this kind of ignorance are profound. In a democracy, informed citizens are the cornerstone of effective governance. Yet, without an understanding of current American policy, how can we expect students to fulfill their civic duties?

One could argue that the information is available to us, all we have to do is take initiative and look for it. But Peter Shulman, an Upper School Social Studies teacher, put it best when he said, “There is a lot going on, and it's complicated…often people are in their information bubbles.”

An anonymous CGS student who emphasized these information bubbles said, “Catlin students are informed on information they want to know.” I think this is true and somewhat exacerbated by our curriculum, but not entirely our fault.

There is so much to know about American policy and so many perspectives to consider and sift through. It’s an incredibly daunting task for one person to “appropriately” inform themselves on all of the policies being pushed by their political party, let alone any other. So why are we leaving this task, one that is crucial to having informed voters and thus an effective democracy, to the initiative of teenagers?

Isn’t it just as important to understand the policies you will be voting for that will affect your future as it is to learn Calculus? Don’t we want to raise a generation of voters who can look at a political party, examine the policies that will be pushed by their administration, and then make a decision on who they support?

Human Crossroads, a class taken by ninth-graders in the Upper School, changed its curriculum after receiving consistent feedback that only left-wing values were topics of discussion in the classroom. As a result, the team of teachers modified the curriculum to include different political perspectives on discussed topics and used sentence stems to teach students how to disagree with one another respectfully during heated conversations.

This is a step in the right direction, but just that, a step. Inviting different political perspectives on social topics invites different policy solutions, but this is something that should be done deliberately in more classes at Catlin Gabel than just Human Crossroads and in classrooms across America.

There needs to be a shift in our approach to civic education. This could look like a federally mandated curriculum in public schools that prioritizes the study of current American policy. One that includes discussions of legislation, executive actions, and Supreme Court rulings about decidedly important issues, as well as their implications for various communities.

But, no matter what the solution looks like, there is no denying that in an age of media sensationalism and partisan echo chambers, we must give students the skills to navigate the complexities of our political landscape.

We must challenge the notion that politics is an abstract concept disconnected from our daily lives. In the words of Thomas Jefferson, "An informed citizenry is at the heart of a dynamic democracy." It's time for all our educational institutions to live up to this ideal and equip students with the knowledge and skills they need to be active participants in our democracy.