Students in the Election Class talk about the causes and solutions of political misinformation

By Maddie Snyder ‘26

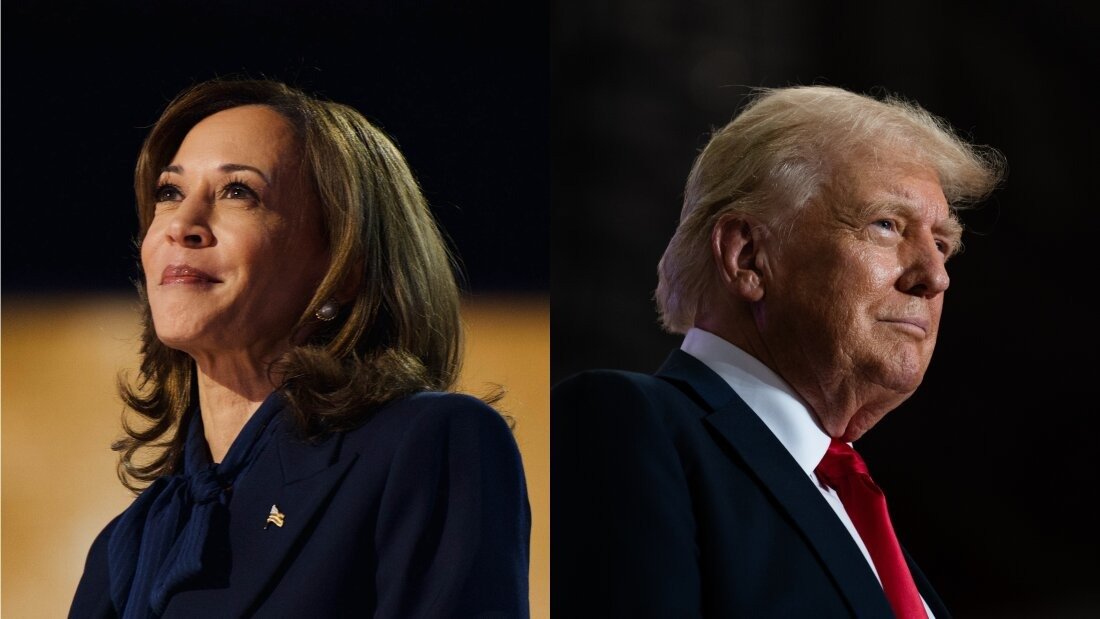

Courtesy of NPR

On Nov.5, 2024, millions of Americans will cast their ballots in the Presidential election after another election cycle filled with misinformation. An issue that has only been amplified by social media and easy access to biased and inaccurate information.

“Misinformation is really spreaded through not understanding common knowledge on issues or not doing research,” said senior Jane Hanson, a student in the 2024 Election class at CGS.

Research into different topics has been a large part of the class thus far. Hanson said research is the solution but can also be a problem.

Finding sources that are unbiased can be challenging. Many political news sites often have a bias, leaning more strongly in one way than another. For example, Fox News leans right and CNN leans left.

Misinformation can also be circulated by politicians explaining that their policy is better than their opponent, without explaining directly why. Information being played up or down to emphasize the point of one side is a large issue Hanson pointed out.

She said the amount of skewed information she encountered made her realize why American politics is so polarized.

Senior Charlie Broad pointed to social media as the root issue for misinformation. Both Harris and Trump have made social media across platforms like Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, and Twitter. The last of which Trump was actually banned from after the January 6th inserection to prevent the risk of “further incitement of violence.”

Broad says though that although these posts are able to alter the thoughts of many Americans they don’t often display the full truth.

“I think this is extremely worrisome because social media is dominated by younger audiences,” stated Broad.. “If so many young people are subject to misinformation when they are young, it could lead to a slippery slope of many soon-to-be voters being miseducated about topics.”

While interviewing voters in Pioneer Square Hanson saw this misinformation come into practice.

“Lots of people claim to know a lot about the election but don’t know about basic concepts like tariffs,” she said. Tariffs, a tax on imported foreign goods, has also been a topic of focus in presidential debates, in Hanson's election class.

One of many topics that required fact-checking during the Sept. debate, when both presidential candidates made claims that were later proven to not be true.

"Donald Trump left us the worst unemployment since the Great Depression," stated Harris, which is untrue. Trump also made many false claims, such as falsely stating that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, OH were eating cats and dogs, which subsequently went viral online. A definitely false statement that had major repercussions;

Following Trump’s statements in the debates. Bomb threats caused the closing of public events and spaces. National Guard troops were even sent to Springfield to escort kids to school due to shooting threats. Thankfully no violence actually occurred in Springfield.

The 2024 election is not unique in its problems with misinformation though. Some may remember after Biden's win in 2020 Trump’s message that the election was “stolen” was widely spread and accepted.

Even after facts had been presented the call for a recount had not quieted. This eventually led to the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol. Over a thousand people stormed the Capitol Building demanding that Congress, which was certifying the election, return the “stolen” election.

Trump’s claims about the 2020 election were since repeatedly struck down as untrue even before Jan. 6.

Broad raised a concern about this when talking about the debate.

“In each debate, there were countless instances of candidates, specifically Trump, that made baseless claims portrayed as fact,” said Broad. “We discussed how [the fact-checking of candidates] might impact the election, but I decided that the loyal base of Trump would often overlook cases of misinformation.”

Hanson believes that classes like the one at CGS could be widely beneficial in combating misinformation.

“I had no political understanding before this class besides just like my parents believed in,” said Hanson. “At this point, I’m teaching my parents about what I learned and why I’m voting for who I’m voting for.”

Broad shares Hanson’s opinion as he believes it is unhealthy for any person’s political intake to be solely from social media and not doing personal research.

“This class has prompted me to dig deeper and explore much more of the political landscape and various elections in the US,” said Broad while reflecting on the impact of the class.

“I still don’t know everything about the election, but I learned so much more and feel more informed, ” said senior Lyla Wohlgemuth. Similar to Hanson, she wasn’t heavily involved in politics but felt much more informed after the class.

Hanson will be one of the millions of Americans voting on Nov. 5. While Broad and Wohlgemuth are not able to vote, Wohlgemuth hopes “that everyone who is able to vote should be as informed as they can be.”