The reality of Asian student misidentification

By Elise Kim ‘25

Graphic by Eva Vu-Stern ‘24

Erin. Lily. Sienna. Lauren. Katie. My name is Elise, but these are just some examples of names I’ve been called by teachers over the years.

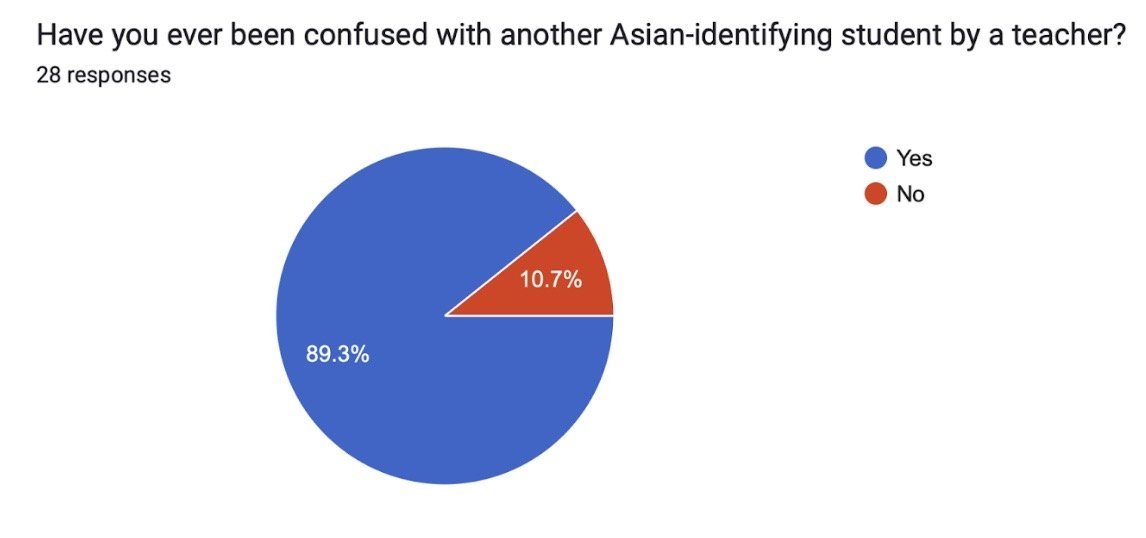

I am not alone in experiencing Asian misidentification. According to an anonymous survey I sent out to 73 Asian-identifying Upper School students (28 responded), 89.3% have been confused with another Asian student by a Catlin Gabel School (CGS) teacher.

Photo by Elise Kim ‘25

The number of times per year respondents of the survey get confused for another Asian-identifying student ranged from 2-3 to 30-40. The average number of times this occurs comes around to about 12 misidentifications per year.

However, this phenomenon is more than just a statistic and can play out in a diverse range of ways. According to most of the Asian-identifying students I interviewed and the respondents of the survey, this misidentification will most commonly occur when a teacher calls on a student but says another Asian student’s name.

One anonymous survey respondent stated that a teacher had called them “someone else’s name multiple times even after they had been teaching us for six months.”

“Recently, one of the subs for one of my classes got three of the Asian girls confused in the same class,” stated junior Erin Chow. “Even though I had said, ‘Oh, my name is Erin,’ she ended up calling me somebody else when they walked into that class.”

Another anonymous survey responder said that they often get congratulated by teachers on another Asian-American student’s accomplishments. They stated, “And I have to be like, ‘No, that’s not me.’”

Reactions from Asian-identifying students vary. According to CGS’ DEI coordinator and developmental psychologist Connie Kim-Gervey, how this phenomenon affects students is “determined by where they are in development and identity, and how important it is that other people see them and know them.”

A large number of students simply feel awkward and confused when encountering this situation. “I don’t think I look like any of my friends who are Asian,” stated Chow. “So just getting that confused is a little off-putting because we don’t really look at all alike. I don’t see how you could get confused between us.”

This is especially the case for students who feel they don’t have a voice and are more hesitant to call out their teacher. “It’s hard for them to say, ‘Hey, that’s not my name,’” said junior Ben Bergstrom. “Then, it’s this spiral of being called the wrong name over and over again. They just have to kind of sit there and take it.”

The majority of the survey respondents and students I interviewed are only mildly affected by this phenomenon. Most stated that they understand that teachers are bound to misidentify students and that this is done without bad intent.

One anonymous survey responder stated, “I don’t mind it because I confuse people as well. Sometimes, it’s just because you didn’t really look at the person and only saw a few details.”

On the other hand, other Asian-identifying students are deeply affected. Some students from the survey described it as “pretty hurtful”, often feeling “unseen, unspecial, and replaceable”.

“I feel a little uneasy that we can all just be so easily confused because somewhere in people’s minds, consciously or unconsciously, we’re all ‘grouped’ up together,” said junior Aditi Subramaniam.

Students' emotional reactions to this phenomenon also depend on how frequently they get confused by the same teacher. “Being confused with someone else isn’t offensive to me,” stated sophomore Vishaka Priyan. “It is only when it becomes a pattern with people who know me that it irks me.”

In addition, some of the students I interviewed and surveyed were conflicted and unsure of how to feel. One surveyed student stated, “...in most cases, teachers have positive intentions, so I feel bad labeling the interaction as a ‘microaggression’ because that seems like I’m insinuating they have racist intentions. But at the same time, it is not something to just ignore, especially when it is a systematic problem that happens so often to so many students of color.”

According to junior Justin Xia, this is further complicated by a larger Asian stereotype that exists in our society: Asians are less willing to speak up for themselves. Xia, when confused with another Asian-identifying student by a former CGS coach, stated his reluctance to “be automatically put into that category”. Yet, he also was worried about the “subtle repercussions” his speaking up would have on his playing time and his perceived value.

“If the coach doesn’t see me as a person enough, where he finds a distinction between me and another player, that’s also a bad thing,” stated Xia. “It put me in a weird, conflicted place because I did want to speak up, but I also didn’t.”

Sometimes, this confusion impacts Asian-identifying students not just emotionally, but academically as well.

Sophomore Katie Jin stated that once her teacher confused her with another Asian-identifying student and told that student her test date got moved up. Jin was not informed of this change. “This hurt because we had gone through 6 months of school and it felt like he wasn’t seeing my individuality,” said Jin. “It also sucked because it completely messed up my test preparation.”

When she tried to talk to her teacher, she got “brushed off.” According to Jin, the teacher insisted he had not mixed her up with another student and told her, “Either way, your test is on Monday.”

Faculty reactions vary, however. Most faculty, as stated by Xia, “backpedal” and try to minimize the mistake with excuses. Examples include teachers pointing out various physical similarities such as “long, black hair”.

It bothers Priyan when teachers state that Asian-identifying students all look alike, especially “when they [faculty] can remember the names of 8 different white and blond girls.”

However, according to the students I interviewed, CGS faculty almost always apologize. “Often at Catlin with the teachers it truly does feel like a mistake and they do feel bad,” stated Subramaniam.

CGS’ Head of Upper School Aline Garcia-Rubio agrees. “I think faculty feel a lot of guilt and sometimes shame when that happens. Nobody wants to make that mistake,” stated Garcia-Rubio.

She explained that often when faculty feel guilt and shame, in that moment, they concentrate on how badly they feel about making that mistake, instead of focusing on how their actions impacted the student and forming plans to make amends.

Garcia-Rubio also emphasized that this phenomenon is not just a faculty issue but a human one. Because of this, Kim-Gervey suggested that the best way to move forward is to veer away from shame and more towards mutual understanding between students and faculty.

“I hate thinking about students feeling lesser because someone has named them incorrectly, and I don’t think that captures the whole story,” said Kim-Gervey. “When teachers or employees make mistakes, staying quiet because of shame only exacerbates the problem.”

At the same time, Garcia-Rubio does not want to minimize the responsibility of educators to know their students and identify them correctly. “In the context of school, the responsibility falls on the adults. We don’t get a pass. We have to work on it,” stated Garcia Rubio.

“We’re all going to have our different human glitches and all educators have to work to deal with the glitches,” she stated. “There are a million ways to go about this.”

First and foremost, it starts with the initial reaction of faculty after they’ve misidentified a student. “The ideal thing is to recognize a mistake has been made and then in a moment, fix it and then also not make a giant deal out of it,” stated Garcia-Rubio. “Then, move on because [if you don’t] you put it on the student to be burdened by the emotion and the repair.”

The students I interviewed agree. An ideal apology for them would be for the faculty member to take accountability for their actions, recognize the harm they may have caused, and then make an effort to not make the same mistake again.

“In the process of repair, when any person makes a mistake of misidentifying anyone else, they need to make an effort to not make the mistake again,” said Garcia-Rubio. “I believe it is as important as the immediate ownership of responsibility.”

Some solutions faculty have found for preventing future misidentifications are putting name tags on the desks for students, hanging up photos for the students every day to use as a reference, or having students state their names before they participate in class.

For Garcia-Rubio, the best way to combat this issue is to “spend time with people that are different from us and really get to know them.” She reasoned that by spending time with those of a different race or ethnicity, names and faces become more familiar. In addition, for her, this minimizes prejudices, misconceptions, and generalizations.

This can be as simple as having a small conversation. “If I spend 15 minutes talking to a student, I will never forget who that person is, or their name,” she said. “I’m not going to confuse who they are.”

However, Subramaniam believes it is up to her classmates to build a culture where misidentification will not be “brushed under the rug” and played off with the same excuse that Asian students “all just look too much alike.”

One thing is clear from discussions with both CGS faculty and students: this phenomenon needs to be more known. Chow hopes with an increase in awareness of this issue it will help “minimize and catch people while they’re misnaming.”

“I think continuing to talk about it… is helpful, so we all remember there’s some humaneness about it, as well as some things we can deliberately try to do to make it better,” emphasized Kim-Gervey.

If you’d like to read more on the topic of misidentification, feel free to check out these additional sources provided to me by Aline Garcia-Rubio.

Why people of color are misidentified so often

There's a thin line between confusing two people of the same race, and bigotry

Ingroup and outgroup differences in facial detection

What drives social in-group biases in face recognition memory? ERP evidence from the own-gender bias