Colonialism is forever, and should be taught as such in the classroom

By Lauren Mei Calora ‘20

Photo by Zoie Calora.

Even though this article is a critical reflection on what it means to me to be Filipino-American and how I’ve learned about my identity in and outside of the classroom, I am proud to be Filipino-American. As I leave this community, I hope my voice and heart can be heard and that other CGS students resonate with parts of this article.

At Catlin Gabel School (CGS), I learned about colonialism as a past event. I had the naive perception that colonialism didn’t impact me or the current world.

In Middle School, I remember when I learned how the United States settled in Native American land. In classes, we acknowledged the process was violent, but I felt like we never connected the past actions of the United States to the position and experiences of Native Americans now.

In Upper School, I remember when I learned about colonialism in the Congo and India. Both the Congo and India were under control of European powers, and we compared the similarities and differences between the Congo and India. We talked about how colonialism took place in both countries, but we didn’t connect it to how colonialism continues to impact these countries.

As described in a National Geographic article on colonialism, “Colonialism is defined as ‘control by one power over a dependent area or people.’ It occurs when one nation subjugates another, conquering its population and exploiting it, often while forcing its own language and cultural values upon its people.” Colonization is the action or process of colonialism taking place.

This past summer, I walked across Spain. I had an eerie feeling of familiarity even though I had never been to Spain. The importance of Catholicism was evident as I followed the Camino de Santiago, and words in Spanish were the same or similar to words in Tagalog, one of the languages my family speaks at home.

I walked through a town called Getaria that featured a statue of a man named Juan Sebastian de Elcano. Elcano sailed to the Philippines as a part of the famous crew led by Magellan. Magellan was killed in the Philippines, so Elcano led the crew back to Spain.

It was intimidating to stare face to face with the statue of a man credited to be a hero in Spain, and also know that Spain had a brutal history of colonization of the Philippines and that this man helped contribute to that.

The Spanish initially ruled over the Philippines semi-passively by imposing forced tributes. However, the Spanish shifted their strategy over time and began to appoint Spanish military powers to oversee the Philippines.

One of Spain’s adamant goals was for complete religious conversion of the people of the Philippines.

“In the first decades of missionary work, local religions were vigorously suppressed; old practices were not tolerated,” says the the Britannica Encyclopedia on the Spanish Period of the Philippines.

As soon as the Spanish established a strong Catholic presence, the church acted both as a pacifier for the Spanish over the Philippines and a bridge to Spanish culture. The church carried a lot of power and influence over everyday Filipino life.

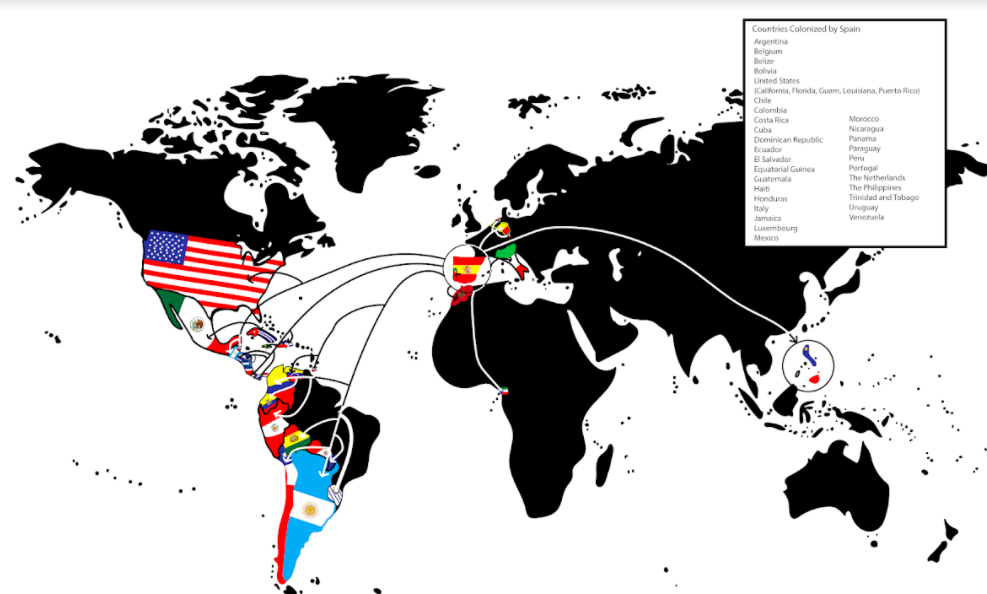

The Philippines isn’t the only country that has felt Spain’s influence through the years. Spain colonized over 30 countries and was one of the largest empires in the world.

Spain also brought Catholicism to other Latin American countries, and in some cases, the colonization was more violent, too.

The Philippines was controlled by Spain for over 300 years, and it forever changed the cultural landscape of the Philippines.

Because of Spain’s influence, over 80% of Filipinos are Roman Catholic.

Dr. Anthony Ocampo is a scholar and writer who wrote “The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race.” Ocampo observed that Filipinos often don’t identify as Asian, so the book explores why this is through interviews with Filipinos in California.

In the process of interviewing Filipinos for his book, Ocampo observed a common theme.

“A lot of people that I talked to were so excited and hungry to have a space, even if it was just a one-hour meet-up at a coffee shop, where they got to talk about what it means to be Filipino,” said Ocampo. “It just struck me how little opportunity Filipinos have to tell our stories on our own terms.”

After conducting his interviews, Ocampo was able to explore patterns between all the interviews and highlight common experiences based on the Filipino identity.

In an interview with NBC news, Ocampo said, “The Spanish colonial period left these marks on Filipino culture—residues that last even today. You have things like religion, our last names, and everyday words in Tagalog and other Philippine dialects.”

Ocampo and his book helped me realize that Spain’s colonization of the Philippines was not historic, and in fact continues to shape everyday life.

Spain helped completely mold the Filipino identity I know today. Both my parents grew up in the Philippines, while I was born and raised in the United States. Everything I learned about Filipino culture I learned from my parents.

My parents raised me to be Roman Catholic, though I’ve chosen to slowly drift away from the religion. They also taught me the importance of celebrating family and food. But through reading Ocampo’s book, I realized that aspects of culture I had always considered Filipino might have actually been Spanish-influenced.

Although most people who know me know I am Filipino and that I identify as Asian, in the past couple years, some people have confused me as being Hispanic. Maybe it was my last name, Calora, or my slightly tanner skin compared to other Asians, but I’ve always subconsciously wondered where the misidentification could’ve come from.

However, my time in CGS classrooms didn’t directly help me explore my Filipino identity.

I’ve been at CGS for almost 14 years, and as I leave, I hope CGS reconsiders how they teach about colonialism in the classroom.

In the fall, I had the opportunity to take a Global Online Academy class called “International Relations” where I was introduced to postcolonialism, and I hope we can incorporate this framework into CGS’ English and history classes.

Sheila Nair describes postcolonialism in “International Relations Theory”: “Postcolonialism examines how societies, governments and peoples in the formerly colonised regions of the world experience international relations. The use of ‘post’ by postcolonial scholars by no means suggests that the effects or impacts of colonial rule are now long gone. Rather, it highlights the impact that colonial and imperial histories still have in shaping a colonial way of thinking about the world.”

A series of CGS experiential learning opportunities led me to find Ocampo’s book, from the global trip to Spain to attending the National Association of Independent School’s Student Diversity Leadership Conference, but I wish I could have learned about my Filipino identity in the CGS classroom.

At CGS, I’ve struggled to feel heard and seen, but as I’ve reflected on my time here, I think seeing myself or learning about aspects of my identity represented in the CGS curriculum would have helped me feel more supported.

I hope CGS considers incorporating Filipino and Filipino-American history into their curriculum. The feeling of finding Ocampo’s book and learning history that directly helped me think about my identity remains unmatched in my educational history.

I asked Ocampo how he convinced people that learning about Filipino and Filipino-American history was important.

“As I’ve gotten older, I’m just drawn to the people who own it. Before I used to be really self-conscious about my Filipino-ness. In some ways, it was just because you’d see people’s faces or they’d roll their eyes, but I’ve figured out a way to be all about it, how to ‘rock it’ in a way that’s infectious,” said Ocampo.

This article is my best attempt at “rocking it” and hoping other people will also find what I have to say interesting and worth learning about.

Similar to how representation in Hollywood or the media is important for people to feel seen and heard, I think representation in education can vastly improve how a student feels and understands their own identity. I am arguing for Filipino and Filipino-American history because that’s what I feel strongest about, but our curriculum should be diverse in considering multiple personal identifiers.

As I sat in history classes, it was really easy for me to distance myself from history and treat it as the “past,” when in reality most of the “past” continues to impact the present.

By defining the connections between past and present more clearly, I think there are more opportunities for personal growth and exploration for students, teachers, and the institution.

I think this is especially important when talking about colonialism.

We learn about colonialism because it’s important to recognize countries’ past actions and learn about the history of the world. But I think connecting colonialism to our current world is equally important because it helps start conversations about historical accountability and cultural identity.

I’m hopeful for the future of CGS, and I’m incredibly grateful for every moment that I was able to explore my identity at CGS.

Even though this article is a critical reflection on what it means to me to be Filipino-American and how I’ve learned about my identity in and outside of the classroom, I am proud to be Filipino-American. As I leave this community, I hope my voice and heart can be heard and that other CGS students resonate with parts of this article.